Humans have an innate sense of justice. From a young age onwards, children recognise and contest perceived injustices. Notions of justice are, however, not universal: they vary between and within societies, influenced by individual beliefs or shared ideologies that co-exist and compete at the same time. Injustice can be observed in cities worldwide: from dispossession and displacement of property to forced evictions, through spatial segregation and related politics of difference to the inequality of access to places of necessity, to racial and gender discrimination. These and many more injustices, which remain ever so present and ever so eruptive, relate to distributional as well as procedural injustice.

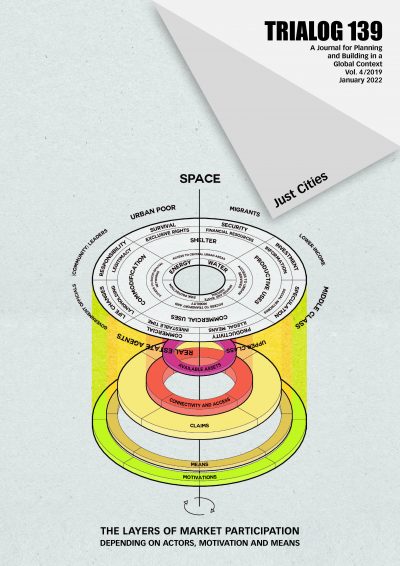

Colin, Wall and Jama go beyond the notion that considers land markets as a key contributor to spatial injustice. According to them, spatial justice can be understood as ‘a process of struggle to lay claim to place or space’. This interpretation of the relationship between land markets and spatial justice sees a ‘competition for participation in which land markets play an enabling role, heavily mediated by and embedded within social structures’. Chalastanis, in his article, decries the Resilient Athens Program as a legitimisation of the austerity policies implemented in Greece, contributing to rather than reducing existing inequalities. However, as a sign of hope, he also identifies ‘communities of struggle’ (Arampatzi 2017) that have emerged to tackle these inequalities, mostly ‘characterised by self-organisation, horizontality, and independence from institutionalised and formal voluntary forms’.

Notions of justice are not absolute; they are layered and subjective. Susan Fainstein, in her writings about the Just City (e.g. in 2010), identifies three core values of the just city: democracy, diversity and equity. At the same time, she recognises the inherent tensions between them: there will be trade-offs between these values as an increase of one could potentially negatively affect another. Similarly, Middelmann, demonstrates that there are elements of exclusion as well as publicness in each of the three public spaces in Johannesburg’s inner city that he used as case study. He observes that Global North critiques of injustices related to privatisation of public space do not necessarily hold in the context of the Global South. While each of the public spaces studied has a different model of ownership and management, he shows that factors other than privatisation, such as history, design or perception, create a dynamic interplay between inclusion/publicness and exclusion.

Khurana and Beier, in their contribution on the redevelopment of the Bombay Development Directorate chawls, point out people’s subjective and frequently conflicting notions of justice. They find that while most people tend to agree on the macro-level justice of the development project, there can be quite different interpretations regarding its modes of implementation at the micro-level. These are reflected to a certain extent in the justification of personal benefits attributed to different groups of residents. This resonates with what Vanessa Watson, who unfortunately passed away recently, identified as ‘(opportunistic) foregrounding of particular values and belief systems, which may change under different circumstances’ (2003: 402).

Fahami & Ziad describe distributional injustices of the housing conditions of the urban poor in Chittagong, Bangladesh, from the perspective of female garment workers. The article highlights how the demanding labour conditions compound on the already poor housing conditions and the neglect of requirements for adequate housing. Moving from housing injustices in Bangladesh to Ghana, Danso-Wiredu focuses on the procedural injustice of the high advance rental charges in Ghana. She points out that the current housing shortage increases the power difference between landlords/ladies and tenants, thereby leading not only to the high rent advance charges but also to evictions, unregulated rent increases, and tenants resorting to living in smaller, congested spaces.

As the articles in this issue suggest, despite and because of different interpretations of justice, a perfectly just city is an illusion. It is important to take different perspectives into account when assessing justice in a city, and/or spatially. We are, therefore, happy to include in this issue the experiences of cycling in the city of Nairobi, as well as a photo essay on challenges for pedestrians in the same city. Among others, it is through these accounts of everyday practices that spatial justice can be glimpsed and just cities can be imagined.

Alexander Jachnow, Els Keunen, Dorcas Nthoki Nyamai

Table of contents

- 05. Urban Land Markets as Spatial Justice Colin Marx, Michael Walls & Jama Musse

- 11. Towards ‘The Right against the Resilient City‘: Insights from Crisis-ridden Athens Dimitris Chalastanis

- 15. Mixed Evidence on Ownership and Management of Public Space: Cases from Inner-city Johannesburg Temba John Dawson Middelmann

- 24. Towering Aspirations and a Loss of Social Space? Dwellers‘ Notions of (In)justice in Social Housing Redevelopment in Mumbai Nayani Khurana & Raffael Beier

- 32. Spatial Injustice in a Lower-Income Working Community: A Study on the Housing Conditions of Female RMG Workers in Chittagong, Bangladesh Mahlaqa Fahami & Abu Sayeed Mohammed Ziad

- 44. The Conceptualisation of the Injustices in the Ghanaian Advance Rental Housing System Esther Yeboah Danso-Wiredu

- 52 . A Pedestrian’s Experience in Nairobi Dorcas Nthoki Nyamai

- 55 . Benefits of Bicycle Commuting – A Nairobi Perspective Martin Macharia

- 56 . Book reviews

- 58 . Call for Book Reviews

- 58 . Call for Editors

- 59 . Obituary for Eike Jakob Schütz