Today, more people are living in urban areas than ever before, and finding adequate ways to manage this growth is proving a challenge. Concepts such as “resilient urban development” and “right to the city” are examples in response to the challenges that our cities are facing. Resilience, as a positive concept, focuses on the capacities of cities and their institutions. These capacities are essential factors for making cities capable of dealing with challenges that arise not only from rapid urban growth, but also from possible sudden shocks disrupting their natural and social systems. In turn, the “right to the city” is a desperate call for social justice, although justice usually falls by the wayside when it comes to ensuring affordable housing and basic urban services in the context of rapid urbanisation.

This issue of TRIALOG highlights selected contributions presented at the June 2018 meeting of the annual TRIALOG conference held in Dortmund, this time with the theme and title: Resilient Urban Development Versus the Right to the City? Actors, Risks and Conflicts in the Light of International Agreements (SDG and NUA). What Can the Academia Contribute? Obviously, the conference could not find a final answer, but it was able to contribute valuable cases and ideas to the broad challenge. The articles in this issue discuss these from different perspectives.

The first four articles underscore bottom-up resilience building and risk management. Maren Wesselow, with her article “In town, everyone is on their own”, discusses the challenges that urban farmers in Dar es Salaam face as they struggle to build their risk management capacity. The subsequent two articles, one by Páez, Díaz, Lizarralde, Labbé and Herazo, and the other by Muñoz, Páez, Lizarralde, Labbé and Herazo, discuss how female-headed households mitigate and adapt to disaster risk in Salgar, Colombia and, respectively, water scarcity on San Andres island. Highlighting the traditional role of women, the authors argue the effectiveness of these strategies for resilience building on the basis that they are measures founded on local needs and capacities in managing risk and water scarcity. Dima Dayoub, in a completely different context, discusses resilience as an inherent character of cities embedded in the survival instincts of people. With that she underlines lessons from war-torn Aleppo with the aim of building the capacity for post-war resilient urbanisation.

In contrast to the former articles, Wiriya Puntub and Juan Du discuss resilience building from a risk-governance perspective. Using the case of informal settlements in Metro Manila, they highlight gaps in the national and regional policy frameworks, and suggest measures that should be taken into consideration to fill the gaps in the policy frameworks and urban planning. Limbumba, Mkupasi and Herslund present lessons learnt from a design charrette process for stormwater management in an informal settlement in Dar es Salaam. The authors discuss non-structural stormwater management measures, and argue the effectiveness of such an approach, in contrast to constructing a drainage system, to build flood resilience in informal settlements.

The articles of Marielly Casanova and Laura von Puttkamer put the focus on the concept of the “right to the city”. Von Puttkamer discusses strategies of residents in Old Fadama (Accra) to resist eviction, and how they protect their right through proactive actions that have changed public opinion about the residents of informal settlements and influenced government decisions on their settlement. At the same time, Casanova discusses the issue of the right to the city from a social-production-of-habitat perspective. Based on the cases of Torre de David in Caracas and Monteagudo in Buenos Aires, she argues that the right to the city, with respect to affordable housing, can only be ensured if the production of habitat also empowers residents to organise themselves and access livelihood opportunities.

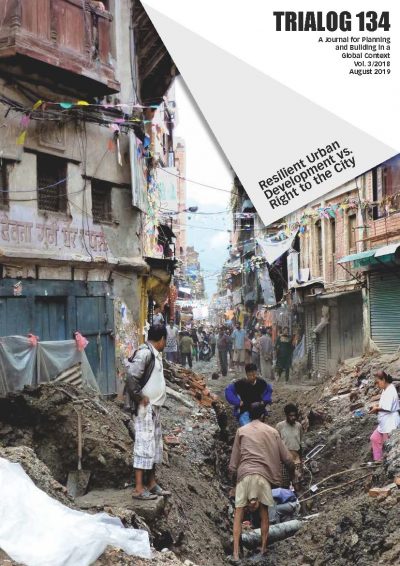

Simone Sandholz and Mia Wannewitz discuss how critical infrastructure influences social resilience. Using the case of the Gorkha earthquake in Nepal, the authors argue that a socio-technical approach is an essential factor to ensure the planning of resilient critical infrastructure.

–

Heute leben mehr Menschen in städtischen Gebieten als jemals zuvor. Es ist eine Herausforderung, Wege zu finden, um dieses Wachstum zu bewältigen. “Resilient Urban Development” und “Right to the City” sind Beispiele für Konzepte, um auf diese Herausforderungen zu reagieren. Resilienz als Konzept konzentriert sich auf die Kapazitäten der Städte und ihrer Institutionen, damit Städte Herausforderungen meistern können, die sich nicht nur aus dem Wachstum der Städte ergeben, sondern auch aus plötzlichen Erschütterungen, die ihre natürlichen und sozialen Systeme stören. Das “Recht auf Stadt” ist ein verzweifelter Ruf nach sozialer Gerechtigkeit, die in der Regel auf der Strecke bleibt, wenn es im Kontext einer schnellen Urbanisierung um die Schaffung bezahlbaren Wohnraums und grundlegender städtischer Dienstleistungen geht.

In dieser Ausgabe werden ausgewählte Beiträge vorgestellt, die auf der Jahrestagung von TRIALOG mit dem Titel Resilient Urban Development Versus the Right to the City? Actors, Risks and Conflicts in the Light of International Agreements (SDG and NUA). What Can the Academia Contribute? im Juni 2018 in Dortmund präsentiert wurden. Die Konferenz konnte keine endgültige Antwort finden, aber wertvolle Beispiele und Ideen beisteuern und die Themen aus verschiedenen Perspektiven behandeln. Die ersten vier Artikel unterstreichen den Aufbau von Bottom-up-Resilienz und Risikomanagement.

Maren Wesselow erläutert in ihrem Artikel “In der Stadt ist jeder auf sich allein gestellt” die Herausforderungen der Bewohner in Daressalam, die städtische Landwirtschaft betreiben, beim Ausbau ihrer Risikomanagementkapazitäten. Die folgenden beiden Artikel von Páez, Díaz, Lizarralde, Labbé, Herazo und von Muñoz, Páez, Lizarralde, Labbé, Herazo behandeln, wie Haushalte mit weiblichem Oberhaupt das Katastrophenrisiko in Salgar, Kolumbien und die Wasserknappheit auf der Karibikinsel San Andres mindern. Die Autoren heben die traditionelle Rolle der Frauen hervor und argumentieren, dass Strategien zur Stärkung der Widerstandsfähigkeit wirksam sind, wenn sie auf den lokalen Bedürfnissen und Kapazitäten im Umgang mit Risiken und Wasserknappheit beruhen. Dima Dayoub diskutiert idiskutiert in einem anderen Kontext die Resilienz als einen inhärenten Charakter von Städten, der in den Überlebensinstinkt der Menschen eingebettet ist. Damit unterstreicht sie die Lehren aus dem vom Krieg zerrissenen Aleppo, um die Kapazitäten für eine widerstandsfähige Urbanisierung nach dem Krieg auszubauen.

Im Gegensatz zu den Artikeln zuvor diskutieren Wiriya Puntub und Juan Du den Aufbau von Resilienz als Risikosteuerung. Anhand informeller Siedlungen in Metro Manila zeigen sie Lücken in den nationalen und regionalen politischen Rahmenbedingungen auf und schlagen Maßnahmen vor, um diese in den Institutionen zu schließen. Limbumba, Mkupasi und Herslund präsentieren anhand einer informellen Siedlung in Dar es Salaam Lehren aus einem Design-Charrette-Prozess für die Regenwasserbewirtschaftung. Die Autoren diskutieren nicht-strukturelle Maßnahmen zur Regenwasserbewirtschaftung und argumentieren, dass ein solcher Ansatz im Gegensatz zum Bau eines Entwässerungssystems die Widerstandsfähigkeit gegen Hochwasser in informellen Siedlungen erhöht.

Die Artikel von Marielly Casanova und Laura von Puttkamer stellen das Konzept des “Rechts auf die Stadt” in den Mittelpunkt. Von Puttkamer erörtert Strategien der Bewohner von Old Fadama (Accra), um sich der Räumung zu widersetzen, und wie sie ihr Recht durch proaktive Maßnahmen zur Veränderung der öffentlichen Meinung und von Regierungsentscheidungen beeinflusst haben. Casanova diskutiert die Frage des „Rechts auf die Stadt“ aus der Perspektive der sozialen Produktion von Lebensräumen. Anhand der Fälle von Torre de David in Caracas und Monteagudo in Buenos Aires argumentiert sie, dass das Recht auf bezahlbaren Wohnraum nur dann gewährleistet werden kann, wenn es auch die Möglichkeit gibt, sich zu organisieren und Existenzgrundlagen zu erschließen.

Simone Sandholz und Mia Wannewitz diskutieren, wie kritische Infrastrukturen die soziale Resilienz beeinflussen. Sie argumentieren am Beispiel des Gorkha-Erdbebens in Nepal, dass ein sozio-technischer Ansatz ein wesentlicher Faktor für die Planung einer belastbaren kritischen Infrastruktur ist.

Genet Alem, Wolfgang Scholz

Table of contents

- 2. Editorial

- 4. "In Town, Everyone Is on Their Own" – Building Informal Risk Management Arrangements Among Urban Farmers in Dar es Salaam Maren Wesselow

- 9. Coping with Disasters in Small Municipalities – Women's Role in the Reconstruction of Salgar, Colombia Holmes Páez, Julia Díaz, Gonzalo Lizarralde, Danielle Labbé, Benjamín Herazo

- 14. Adaptation to Water Scarcity – Water Management Strategies Led by Women on the Caribbean Island of San Andres Lissette Muñoz, Holmes Páez, Gonzalo Lizarralde, Danielle Labbé, Benjamín Herazo

- 19. Resilient Urbanisation in the City of Aleppo during the Protracted Syrian Conflict Dima Dayoub

- 23. Disaster Risk Governance and Urban Resilience of Informal Settlements – Findings and Reflections of a Multi-stakeholder Participatory Gap Analysis Workshop in Metro Manila Wiriya Puntub, Juan Du

- 28. Participatory Stormwater Management – Lessons from a Design Charrette in Informal Settlements in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Tatu M. Limbumba, Martha J. Mkupasi, and Lise B. Herslund

- 34. Changing the Perception of Informal Settlements from Within – A Case Study of Old Fadama in Accra, Ghana Laura von Puttkamer

- 39. Principles from the Social Production of Habitat as the Basis for the Re-conceptualisation of Social Housing in Latin America Marielly Casanova

- 45. Access to Critical Infrastructures – Driver of Resilient Development Simone Sandholz, Mia Wannewitz

- 50. Book Reviews / Neue Bücher

- 52. Forthcoming Events / Veranstaltungen