Destroyed cities do not only need to rebuild their physical urban environment, they also need to (re)organise their social fabric, secure their economic future, and in many cases (re)construct their place identities. But where do they start in the process of planning recovery and reconstruction? What processes are implemented? Which actors are involved, and in what ways does the level of destruction and the subsequent planning/decision-making affect the future of these cities? In the midst of an ongoing destructive war in Europe, as well as in the context of more-frequent natural catastrophic events taking place around the world, planning recovery and reconstruction are research topics requiring renewed, urgent attention.

On the one hand, war causes major and highly complex disruptions for a city, ranging from its infrastructure to the livelihoods of its inhabitants. On the other hand, war appears to be a major catalyst for urban change. Hence, there is still much to be studied in the field of post-war planning, reconstruction, and recovery. Existing literature has investigated this topic through several lenses: architecture, urban archaeology, heritage, urban design, city planning, critical cartography, and social geography. Researchers have documented and quantified the number/type of bomb attacks on selected cities and the subsequent damage caused, examined reconstruction efforts, alternative planning visions and designs and their legacies, and more recently shifted the focus to the maps of war, critically delineating and ‘reading’ their production and purpose, as well as the information they represent and communicate. This double issue builds on this work, extending the existing knowledge base, widening the geographical focus, and advancing understanding of the disparate intentions, strategies, and logics of city reconstruction and post-war urban planning and their legacies on today’s cities. In doing so, it provides a critical statement on urban planning and the rebuilding of cities/countries and their communities affected by the aftermath of war and disaster.

Using the case of post-war Britain and Ireland, Congreve discusses how, through the New Jerusalems project, a new evidence base is being developed and made available to researchers of the New Town movement, offering a significant new resource for researching, for example, the impact of housing and urban design on public health.

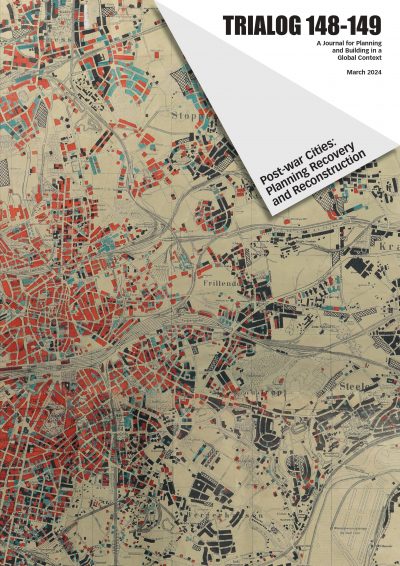

Sedlmeyer, similarly, explores how recent research in the field of Second World War damage maps has resulted in the discovery of a rich collection of unstudied archival material across Germany. He investigates the alternative interpretations and missing information, and critically questions the maps’ backgrounds, intentions, and accuracy.

Mathortykh explores the representation of war destruction, and the planning of post-war reconstruction and recovery, via digital forms of mapping. Presenting several digital mapping projects, he shows how the destruction of Ukrainian cities and the general impact of contemporary wars on urban spaces can be tracked.

Using GIS and an urban analytics approach, Alvanides and Ludwig show how information can be extracted from past records of damage and can be converted into spatial data that can be visualised and analysed with a GIS. This method allows researchers to operate with the information found in maps in novel ways, providing new ways to analyse post-war cities.

Bertram explores the reconstruction process of Belfast, a city severely affected by the Northern Ireland conflict, and that is still segregated and fragmented in some parts. She evaluates and debates the ways in which the reconstruction efforts were designed to change the city’s image, through a vision of ‘normalisation’.

Building on the notion of city image, Gierko investigates how the geopolitical border changes affecting Popowice, in Wrocław, and the ensuing will to (re)construct a Polish identity, impacted the subsequent reconstruction efforts.

Examining Skopje’s reconstruction after the earthquake in 1963, Korolija and Pallini explore the debates and alternative scenarios proposed for the future development of the city, and the nexus between the gigantism of planned architectural projects, the technicalities of town planning, and the basic demands of the present for emergency accommodation.

Using the example of conflict in Aleppo, Syria, Laue traces the emergence of formal and informal pre-conflict networks and collaborations, as well as their potential in post-conflict recovery efforts. She discusses the role of continuous international discourses and expert networks, and the need for a coordinated exchange between all involved stakeholders.

In the context of the long aftermath of the Arab Spring revolutions and associated armed conflict in Benghazi, Libya, Serag emphasises the need for a ‘framework for intervention’ and international engagement and collaboration, which he argues is vital for effective planning, investment/ access to funding, and to build upon existing knowledge/ past experience.

Finally, Rizk explores, through the lens of social capital, the governance of recovery and reconstruction using the examples of Beirut’s post-war recovery in 1992 and the post-explosion recovery in 2020.

Carol Ludwig, Seraphim Alvanides & Franziska Laue

Inhalt

- 4. New Jerusalems: Post-war New Town Archives in Britain and Ireland Alina Congreve

- 9. The Legacy of Second World War Bomb Damage on the Social Fabric of Essen Seraphim Alvanides and Carol Ludwig

- 19. Post-conflict Recovery Discourse for Urban Cultural Heritage in Aleppo. Tracing the Continuum of Exchange between Syria and Germany Franziska Laue

- 28. A Post-conflict Reconstruction Attempt in Benghazi, Libya. The Case of Al-Manara Palace Yehya Serag

- 35. Multi-fold Perspectives on Skopje’s Reconstruction. Megastructures, Infrastructures, and Emergency Housing Aleksa Korolija and Cristina Pallini

- 45. Tracing the Historical Process of Recording and Mapping War Damage. The Cases of Hamburg, Nuremberg and Hanover Georg Sedlmeyer

- 51. Reconstructing and Re-imaging after Protracted Intrastate Conflict. Visions and Realities in Belfast after the Good Friday Agreement Henriette Bertram

- 57. The Day Shall Come Again. How Digital Maps Are Used for Tracking Damage and Planning Recovery for Wartorn Ukrainian Cities Mykola Makhortykh

- 66. The Disaster Recovery of Beirut. The Reconstruction of 2020’s Community-Based Initiatives and 1992’s Public-Private Partnerships Angie Rizk

- 73. Sewing the City Together. The Impact of War Destruction and Post-war Planning on the Contemporary Landscape. An Example from Popowice, Wrocław Aleksandra Gierko

- 80. Book reviews

- 81. Obituary

- 83. Editorial (Deutsch)