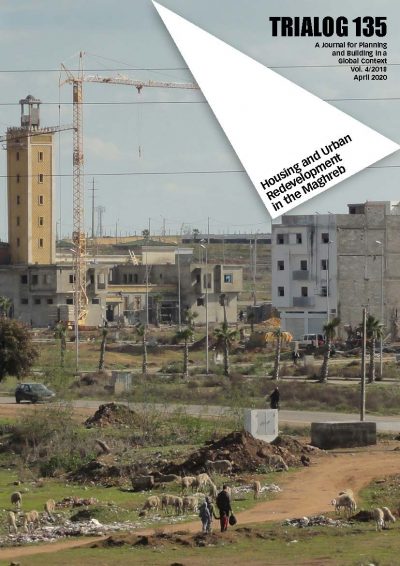

Since the turn of the millennium, Maghreb countries have experienced scores of ambitious housing and urban redevelopment projects of national as well as international scope. Housing programmes which attempted to address the chronic housing shortage through the construction of new towns and the implementation of resettlement and upgrading projects have exacerbated an urban sprawl that continues to put pressure on urban and peri-urban land. These dynamics have also triggered an aggressive competition for land between ‘world-class’ urban redevelopment projects and the politically undesired populations threatened by forced eviction. Thus, the relationship between the city centre and the periphery is shifting. While city centres are being beautified and renewed following global ‘world-class’ aspirations, thousands of citizens are being pushed to spatially disconnected new towns at the urban peripheries.

In this issue of TRIALOG, we focus on these urban contrasts as evident in the Maghreb, and particularly visible in Morocco. They are representative of new urban realities in a region that struggles to cope with a volatile economic, political, and social context.

Almost ten years after the beginning of the Arab uprisings, governments throughout the Maghreb region are still under pressure to respond to people’s demands for access to human rights and social justice. In response, Morocco’s state authorities made access to adequate housing a constitutional right and, likewise, uses social housing policy as an effective governmental tool to prevent further uprisings. As such, housing and urban redevelopment throughout the Maghreb region play a primary role in renegotiating the role of the state and in producing new imaginaries of development and modernity at the level of everyday urban life. In this context, the articles focus on three major topics: 1) the making and promotion of ‚world-class‘ urban megaprojects, 2) the failure of housing programmes to achieve their own policy objectives, and 3) the everyday life experience in rapidly changing urban contexts.

Regarding the first theme, the article by Wippel offers a detailed analysis of the redevelopment of Tangier from a secondary city in the long-neglected north of Morocco to the country’s second most-important economic hub, now hosting Morocco’s largest international harbour. Following the expansion of its port and Tangier’s renewed economic significance, the city has become a site for political investment, as evidenced by the redevelopment of its waterfront and the construction of new large-scale infrastructure. However, Wippel also illumines the shadow of these world-class aspirations, emphasising the forced evictions, enhanced socio-spatial segregation, and injustices of opaque top-down planning. In a similar vein, the contribution of Aljem and Strava on urban megaprojects in Casablanca emphasises how urban megaprojects tend to overlook local needs. Driven by global neoliberal forces, planners do little to hide that prestige projects such as the waterfront development Casa Marina and the luxurious Casa Anfa are exclusively addressed to a wealthy upper class. Consequently, these projects enhance socio-spatial inequalities within the metropolitan area. Looking at patterns of spatial inequality, the contribution of Frikech and Tenzon offers a more-historic perspective. Focusing on the Kenitra-Meknes corridor, the authors look at the development of top-down urbanisation under colonial rule. They argue that historic planning continuities must be considered as elementary conditions of today’s urban centralities and capitalist urban growth.

The article by Beier examines the second major theme of this issue, namely the failure of housing projects to achieve the objective of delivering affordable and formal housing to shantytown dwellers. Focusing on a case study from Casablanca, Beier argues that although many residents could afford moving to new houses, their new legal status remains contested. Most new home ‚owners‘ lack full property titles, and many still access basic services and infrastructure in an informal way. Another failed housing policy is the concept of social mixing, which Chinig addresses in his paper. Using rich qualitative and ethnographic data from a resettlement project in Salé, Chinig argues that moving people of different backgrounds to the same neighbourhood does not necessarily produce a socially mixed neighbourhood. Instead, everyday interactions and differentiated ways of spatial appropriation, as well as segregating building and planning structures, can create multiple subdivisions and barriers within a neighbourhood.

Spatial appropriation also plays a crucial role in the establishment of street markets, which is shown by Grüneisl. Exploring the third major theme of the issue, the author offers ethnographic insights into everyday practices of place-making in the Bab El Falla market in the medina of Tunis after the uprisings and argues that market-making is an ongoing process based on social networks, interdependencies, and competition. The contribution of Belkebir looks at how social networks and everyday interactions among neighbours are impacted by forced resettlement. Focusing on ethnographic fieldwork in the peri-urban town of Ain El Aouda in the metropolitan area of Rabat, she argues that many resettled residents would have wished to stay with their former neighbours. As found in Chinig’s article, mistrust is common among people of differing socio-economic status and residential background. Behbehani, Bassett and Radoine focus on resettled residents‘ everyday practices in the new towns Tamesna and Tamansourt. The authors’ special attention is on economic informalities that have appeared for both reasons of survival and as a form of urban co-production. While authorities keep fighting urban informal markets, many residents see them as a distinct aspect of Moroccan culture, a source of urban prosperity, and a means of appropriating uniformly designed housing blocks.

Raffael Beier, Gerhard Kienast, Yassine Moustanjidi and Sonja Nebel

Inhalt

- 4. Re-Developing Tangier: The Globalisation of a Secondary City and its Local Consequences Steffen Wippel

- 12. Casablanca’s Megaprojects: Neoliberal Urban Planning and Socio-Spatial Transformations Sanae Aljem and Cristiana Strava

- 20. Historical Perspectives on the Emergence of Dispersed Urban Growth in Morocco: The Kenitra-Meknes Urbanisation Corridor Sara Frikech and Michele Tenzon

- 27. Resettlement and Persisting Informality in Casablanca Raffael Beier

- 34. Strategies of Social Mixing and Social Distance in a New Neighbourhood: The Case of Lotissement Said Hajji in Salé, Morocco Soufiane Chinig

- 42. From Fruit to Fripe Trading: Exploring Urban Change in a Tunis Marketplace Katharina Grüneisl

- 48. Neighbourhoods and Post-housing Territorial Appropriation(s) in a Peri-urban Context: The Case of the Attadamoune Neighbourhood in Ain El Aouda, Morocco Salma Belkebir

- 57. The Role of the Informal Sector in New Town Development: The Case of Morocco Fatmah M. Behbehani, Ellen M. Bassett and Hassan Radoine

- 66. Editorial (Deutsch)

- 67. Forthcoming events / Veranstaltungen